DELAYS MITIGATION & CONSTRUCTIVE ACCELERATION

Delay Mitigation and Constructive Acceleration

Definitions

Acceleration: Work by the contractor that is required to complete all or a portion of the contracted scope earlier than scheduled. The accelerated work may be required as a result of:

1. Direction of the owner or its agents (directed acceleration);

2. Conduct of the owner or its agents without explicit direction (constructive acceleration); or

3. Events within the responsibility of the contractor resulting in possible delay that the contractor decides to mitigate.

Directed Acceleration: Formal instruction by the owner directing the contractor to:

1. Complete all or a portion of the work earlier than scheduled.

2. Which directs the contractor to undertake additional work. or,

3. Perform other actions so as to complete all, or a portion, of the contract scope of work in the previously scheduled timeframe. This could include mitigation efforts that usually have no costs associated with them.

Constructive Acceleration:

1) A contractor's acceleration efforts to maintain scheduled completion date(s) undertaken as a result of an owner's action or inaction and failure to make a specific direction to accelerate.

2) Constructive acceleration generally occurs when five criteria are met:

1. Contractor is entitled to an excusable delay.

2. Contractor requests and establishes entitlement to a time extension.

3. Owner fails to grant a timely time extension.

4. Owner or its agent specifically orders or clearly implies completion within a shorter time period than is associated with the requested time extension. and,

5. Contractor provides notice to the owner or its agent that the contractor considers this action an acceleration order.

Acceleration is said to have been constructive when the contractor claims a time extension but the owner denies the request and affirmatively requires completion within the original contract duration, and it is later determined that the contractor was entitled to the extension.

The time extension can be for either additional work or delayed original work.

Constructive acceleration occurs when the contractor is forced by the owner to complete all or a portion of its work ahead of a properly adjusted progress schedule. This may mean the contractor suffers an excusable delay but is not granted a time extension for the delay.

If ordered to complete performance within the originally specified completion period, the contractor is forced to complete the work in a shorter period either than required or to which he is entitled. Thus, the contractor is forced to accelerate the work.

Acceleration following failure by the employer to recognize that the contractor has encountered employer delay for which it is entitled to an EOT (extension of time) and it is requiring the contractor to accelerate its progress in order to complete the works by the prevailing contract completion date. This situation may be brought about by the employer's denial of a valid request for an EOT or by the employer's late granting of an EOT.

Constructive acceleration is caused by an owner failing to promptly grant a time extension for excusable delay and the contractor accelerating to avoid liquidated damages.

Disruption: An interference (action or event) with the orderly progress of a project or activity(ies). Disruption has been described as the effect of change on unchanged work which manifests itself primarily as adverse labor productivity impacts. Schedule disruption is also any unfavorable change to the schedule that may, but does not necessarily, involve delays to the critical path or delayed project completion.

Disruption may include, but is not limited to, duration compression, out-of- sequence work, concurrent operations, stacking of trades and other acceleration measures.

Out-of-Sequence Progress: Work completed for an activity before it is scheduled to occur. In a conventional relationship, an activity that starts before its predecessor completes shows out-of- sequence progress.

Delay Mitigation: A contractor's or owner's efforts to reduce the effect of delays already incurred or anticipated to occur to activities or groups of activities. Mitigation often includes revising the project's scope, budget, schedule or quality, usually without material impact on the project's objectives, in order to reduce possible delay. Mitigation usually has no associated costs.

Recovery Schedule: A special schedule showing special efforts to recover time lost for delays already incurred or anticipated to occur when compared to a previous schedule. Often a recovery schedule is a contract requirement when the projected finish date no longer indicates timely completion.

General Considerations

Differences between Acceleration, Constructive Acceleration and Delay Mitigation.

In practice there are subtle distinctions between acceleration, constructive acceleration and delay mitigation. For example, acceleration cost implies additional expenditure or money for recovery for an incurred or projected delay, and efforts to complete early. The term constructive acceleration applies to expenditure of money for efforts to recover either incurred or projected delay. Delay mitigation, refers to no-cost recovery efforts for incurred or projected delay.

In the case of acceleration, constructive acceleration, and delay mitigation, affected activities are usually on the projected critical path, thus the objective of most acceleration or mitigation is to recover for anticipated delay to project completion.

However, acceleration, constructive acceleration and mitigation can occur with regard to activities that are not on the critical path. For example, an owner might insist that a certain portion of the work be made available prior to the scheduled date for completion of that activity. The contractor may mitigate non-critical delay by resequencing a series of non-critical activities to increase the available float.

There are circumstances in which acceleration measures are used in an attempt to complete the project earlier than planned. Those circumstances are usually classified as:

(1) directed acceleration where the owner directs such acceleration and usually pays for the associated additional cost; or

(2) voluntary acceleration in which the contractor implements the plan on its own initiative in the hope of earning an early completion bonus. Contractor efforts undertaken during the course of the project to recover from its own delays to activities are generally not considered acceleration.

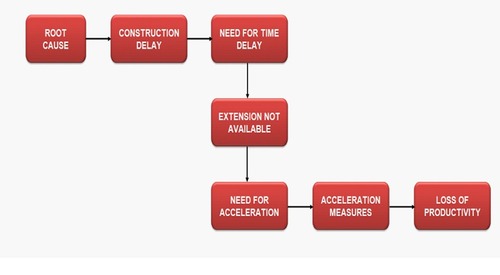

The causative link between a delay event and cost associated with constructive acceleration is diagramed below . The root cause of the impact results in a construction delay or projects a construction delay. This, in turn, results in the contractor identifying that it needs a time extension and requesting a time extension.

The owner denies the time extension request but the need for recovery from the delay remains.

The contractor then undertakes acceleration measures that could include increased labor. Increased labor, without a time extension can result in loss of productivity.

A contractor's cost for acceleration, whether directed or constructive, is generally associated with its effort to engage more resources to perform the work during a unit of time than it had planned. These increased resources fall into the following major categories:

(1) increased management resources;

(2) increased equipment usage;

(3) increased material supply; and

(4) increased labor.

The greatest cost associated with acceleration is usually labor. Since the amount of actual work remains unchanged in most acceleration efforts (the planned scope of work has not increased), the increase in labor cost is a result of a decrease in labor productivity.

Decreased labor productivity is caused by disruption to the planned sequence and pace of the labor. The greater the disruption to the work is, the greater the inefficiency.

Disruption is the result of having more men working in the planned area during a specific time, or loss of productivity associated with individual workers working more hours than planned.

Acceleration and Compensability

Directed acceleration is always compensable to the contractor, although the parties may disagree on quantum. This is true regardless of whether the contractor is accelerating to overcome an owner-caused delay, or to recover from a force majeure event.

Constructive acceleration follows this same pattern. If entitlement to constructive acceleration is established, the contractor may recover for a delay caused by the owner that the owner has refused to acknowledge and also for a force majeure event.

This is different than the normal rule concerning damages associated with force majeure events. Typically, force majeure events entitle the contractor to time but no money. In a constructive acceleration situation, however, the owner has refused to acknowledge a delay, so the contractor has no choice but to accelerate so as to avoid the delay. As a result, the contactor is entitled to recover its cost for that constructive acceleration.

Delay Mitigation and Compensability

Delay mitigation is generally achieved through non-compensable efforts. These efforts are usually associated with changes in preferential logic so as to perform the work in a shorter timeframe.

Mitigation applies to either incurred or predicted delays. There is no mitigation associated with efforts to complete early. Delay mitigation does have a small cost that is usually ignored. This cost is associated with the contractor's management of the schedule and the overall project and is generally considered minimal and, therefore, not compensable.

Elements of Constructive Acceleration

1. Contractor Entitlement to an Excusable Delay

The contractor must establish entitlement to an excusable delay. The delay can be caused by an action or inaction on the part of the owner that results in delay and would be considered compensable, or if can be a force majeure event.

Generally, is the contemporaneous development of a schedule that reasonably shows the basis for the entitlement to the delay. In theory, a contractor can recover for constructive acceleration for work yet-to-be done.

In this situation the owner takes some action that will result in the contractor expending acceleration costs to recover from the delay.

The contractor could assert its entitlement even though the actual acceleration has yet-to occur and the actual acceleration costs have yet-to occur.

In practice, since constructive acceleration occurs after the owner has denied a time extension, it is almost always resolved after the acceleration is complete and the contactor usually is arguing that it was actually accelerated.

Contractor Requests and Establishes Entitlement to a Time Extension

The contractor must ask for a time extension associated with the owner's action or the force majeure event. In that request, or associated with that request, the contractor must establish that it is entitled to a time extension. The owner must have the opportunity to review the contractor's request and act upon it.

If the contractor fails to submit proof of its entitlement to a time extension, the owner is able to argue that it was never given the opportunity to properly decide between granting a time extension or ordering acceleration. The level of proof required to be submitted must be sufficient to convince the owner that the contractor "established" its entitlement.

In certain situations, it is possible that actions of the owner may negate the requirement for the contractor to request a time extension or establish its entitlement. In this situation, the theory is that the owner has made clear through its actions that it will absolutely not grant a time extension.

Owner Failure to Grant a Timely Time Extension

The owner must unreasonably fail to grant a time extension. This is closely related to the requirement that the contractor establish its entitlement to a time extension. If the owner reasonably denies a request for time, as eventually decided by the trier of fact, then by definition the contractor has failed to prove entitlement. Therefore, the owner's decision not to grant a time extension might be unreasonable.

Implied Order by the Owner to Complete More Quickly

The owner must also, by implication or direction, require the contractor to accelerate. There are several different factual alternatives possible . First, a simple denial of a legitimate time extension, by implication, requires timely completion and thus acceleration.

If this denial is timely given, the contractor can proceed. However, the best proof for the contractor is a statement or action by the owner that specifically orders the contactor meet a date that requires acceleration.

Second, the owner could deny the time extension request and remind the contractor that he needs to complete on time. This is better than the alternative mentioned above, but not as strong as the next alternative.

Third, the owner could deny the time extension request and advise the contractor that any acceleration is the contractor's responsibility. This is probably the best proof for this aspect of constructive acceleration. All three of these alternatives meet the test for an owner having instructed acceleration.

Examples of owner actions that meet this requirement include:

(1) a letter from the owner informing the contractor that he must meet a completion date that is accelerated;

(2) an owner demand for a schedule that recovers the delay; or

(3) the owner threatening to access liquidated damages unless the completion date is maintained.

A fourth alternative arises when the owner is presented with a request for a time extension but fails to respond. The contractor is faced with either assuming it will be granted a time extension, or accelerating. Under this alternative, the owner's failure to timely decide, functions as a denial which might be detrimental.

Contractor Notice of Acceleration

The contractor must provide notice of acceleration. As with any contract claim for damages, the owner must be provided notice of the claim. Even though the contractor has requested and supported its application for a time extension, the contractor must still notify the owner of its intent to accelerate or is actually experiencing ongoing acceleration. This is so the owner can decide if it actually desired acceleration to occur or instead the owner may decide to grant a time extension.

Proof of Damages

The contractor must establish its damages. For loss of productivity claims, the contractor is faced with developing convincing proof of decreased productivity. Actual acceleration is not required. A valid contractor effort to accelerate, supported by contemporaneous records, is sufficient to establish constructive acceleration. It is quite common that contractors accelerate to overcome delays but continue to be impacted and delayed by additional events and impacts that actually result in further delay to the project.